Life as just a head on a stick, propped in a corner of the garage, isn’t much. I suppose it’s better than being just a head on a stick, say … in an outhouse, with a roll of toilet paper jammed on your nose.

Even so, you’re still just a head on a stick. And so was poor, poor Pariah. For six long years she peered from her corner behind the step ladders. An innocuous presence, her derelict existence perfectly depicted the essence of her name while her two sisters, Calamity and Infamy, enjoyed a heightened status of being heads on much longer sticks.

I’ts a tossup whether or not building a body for Pariah has contributed to her existential beauty, but there were always supposed to be three Grim Sisters.

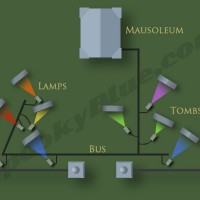

Shadow Wood Cemetery, nestled in the heart of Spooky Hollow, boasts a growing population that enjoys an active nightlife. A pair of flickering LED “gaslight” lamps ensures that everyone finds his way home before sunrise.

Lots, and solutions range in complexity, from our fairly pedestrian driver circuit, to more complicated arrangements that include timer chips, logic gates, and even a programmable logic controller. As it turns out, making an LED turn on and off in a seemingly arbitrary pattern is a complex task, and the more random-looking the effect, the more you approach a Rube Goldberg device.

We’re all about economy here at the skunk works, and what’s more economical than robbery? For instance, the ubiquitous flickering LED candle already contains its own flicker circuit, miniaturized and encased inside the LED. We’re going to swipe that functionality and use it to drive three Ultrabright LEDs.

We’re all about economy here at the skunk works, and what’s more economical than robbery? For instance, the ubiquitous flickering LED candle already contains its own flicker circuit, miniaturized and encased inside the LED. We’re going to swipe that functionality and use it to drive three Ultrabright LEDs.

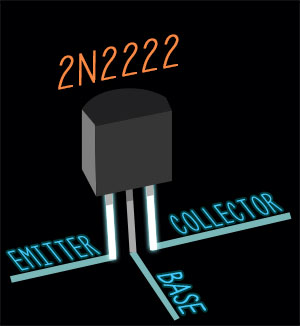

To accomplish this, we’ll be using the good ol’ 2N2222 NPN transistor and a handful of resistors. Well, fewer than a handful; three, to be precise. And we’re all about precision here at the skunk works; next to economy, that is. Economy and precision. Yes, that’s what we’re about.

Perhaps the better question is “why on earth do I care?”

Because Homo erectus dreamed about bar-B-Q, and discovered fire. Further innovations followed, and soon we had flash lights and space shuttles. That’s not to say that Ogg, the inquisitive caveman, triumphantly waving his flaming log around, didn’t get chased out of the cave with sticks.

The point being; a little technology goes a long way, and the benefits of learning something new almost always outweigh the possibility of getting chased with sticks. Call it an occupational hazard.

In simplest terms, a bipolar transistor is a current-controlled device that is generally used as a switch or an amplifier. It consists of three sections called the base, the collector, and the emitter.

In simplest terms, a bipolar transistor is a current-controlled device that is generally used as a switch or an amplifier. It consists of three sections called the base, the collector, and the emitter.

NPN transistor

As current increases at the base, the transistor starts to conduct electricity from the collector to the emitter. The more current at the base, the more current flows out the emitter. Decrease the base current and the emitter current decreases. This is how we’ll vary the brightness of our LEDs.

PNP transistor

Although we’re not using this type of transistor, it’s worth mentioning that a PNP transistor works completely bass-ackwards from the NPN variety. It only turns on when there is no current at the base, and current flows from the emitter to the collector. Where the NPN transistor is triggered by a high signal, the PNP is triggered by a low signal (ground).

Flickering LED amplifier circuit

In both transistor types, a small amount of current can be used to switch a larger amount of current, which is exactly what we’re doing.

Current reaches the base of the 2N2222 transistor through the flicker LED. The amount of current is varied by the LED’s internal circuitry. When the flicker LED reduces the current at the base, less current flows out the emitter, and the ultra-bright LEDs grow dim. When the flicker LED allows more current through to the base, an increase in emitter current causes the ultra-brights to grow brighter.

Current reaches the base of the 2N2222 transistor through the flicker LED. The amount of current is varied by the LED’s internal circuitry. When the flicker LED reduces the current at the base, less current flows out the emitter, and the ultra-bright LEDs grow dim. When the flicker LED allows more current through to the base, an increase in emitter current causes the ultra-brights to grow brighter.

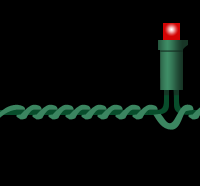

Our flickery little flap-happy runs on 12VDC, which is fairly easy to come by. We power ours with a recycled low voltage landscape light transformer. Mount one or two of these guys inside a lantern, hurricane lamp, or that beat up solar “garden light” you’ve been saving in a box out in the garage. If your lamp’s globe is clear glass or plastic, lightly mist with white spray paint to act as a diffuser. This would look pretty cool behind a “Fresnel Globe”.

He overcame obstacles, and not just of the technical kind, because he almost surely faced a superstitious crowd. Douglas Adams described this reaction to technology in the following set of rules …

Despite getting chased with sticks, Ogg understood technology as a means to an end. This point wasn’t lost on Adams, who, in addition to his rules listed above, also observed, “We are stuck with technology when what we really want is just stuff that works.”

I’m fond of the LED candle amplifier project, and I encourage anyone who likes to sling solder to give it a go. All you really need is patience, time, meticulous attention to detail, and a decent insurance policy.

Or if what you really want is just stuff that works, order a few dozen of these.

I think the secret to a successful blog is to write only about five articles a year. Your traffic, if you ever had any, will fall through the floor, and that really takes the pressure off.

This makes perfect sense to anyone who has ever been labeled a curmudgeon. If it doesn’t describe you, however, then my definition of “successful” is almost certainly different from yours, in which case you should probably just ignore that first bit altogether.

If you’re just joining the party, we are transforming LED Christmas lights into a 12V haunt lighting system. In part I, we touched on the genesis of this project. Part II covered some LED basics, and in this third and final part, we tackle the wiring, lamp construction, and a few other bits that should be helpful if you decide to build your own LED haunt lights.

Prep the wire

Prep the wireYou’ll need at least one spool of LED Christmas lights that you don’t mind destroying. It’s easier to work in sections, so unspool about four feet and snip all three wires. Yes, there are three wires, and you’ll notice the middle wire connects every nth LED. Snip this middle wire about an inch from every LED to which it is connected, then unravel these longer wires and set them aside. They will come in handy later. You’ll have a pretty good pile of extra wire before long, so toss the pieces into a shoe box, or a bucket.

Yes, there are three wires, and you’ll notice the middle wire connects every nth LED. Snip this middle wire about an inch from every LED to which it is connected, then unravel these longer wires and set them aside. They will come in handy later. You’ll have a pretty good pile of extra wire before long, so toss the pieces into a shoe box, or a bucket.

You should now have a strand of LEDs on a single wire. Separate them by snipping the wire halfway between each LED. When you’re finished, you’ll have a small stockpile of LEDs, most with two leads, and a handful with three leads. Trim the leads so they’re all the same length and strip about 1/2″ of insulation from the ends. Repeat until you get bored.

As we discussed in Part II, LEDs are polarized. Current will only flow through an LED when the negative lead is connected to the negative side of the voltage source. You’ll need to identify the positive and negative sides. There are several ways to do this.

As we discussed in Part II, LEDs are polarized. Current will only flow through an LED when the negative lead is connected to the negative side of the voltage source. You’ll need to identify the positive and negative sides. There are several ways to do this.

What about the lights with three wires sticking out of them? The third wire is connected to one side or the other (+ or -), which means you’ll have two negatives, or two positives. Pick one and snip it close to the base. Problem solved.

Once you’ve determined the polarity of your leads, mark one of them. I marked all my positives with a silver Sharpie. If you’re lucky, the plastic casing will have a clip, or some other mark, that is always on the same side. If so, then use this as a clue to mark the other leads; it’s not necessary to check polarity on the rest of the LEDs.

For our cans, we chose 2″ PVC pipe, cut into lengths of about six inches. If you are adept at making straight cuts with a hacksaw (I’m not), then this will be a snap. If you have a large ratcheting pipe cutter (I don’t – yet), then even better. If you decide to cut your PVC using a table saw (I did), then I can’t stress enough the importance of observing every safety precaution you ever heard of, up to, and including, wearing a lacrosse helmet over a hockey mask. See exhibit A below, which illustrates the effects of “kick-back”, and very nearly compromised the bilateral symmetry of my face.

For our cans, we chose 2″ PVC pipe, cut into lengths of about six inches. If you are adept at making straight cuts with a hacksaw (I’m not), then this will be a snap. If you have a large ratcheting pipe cutter (I don’t – yet), then even better. If you decide to cut your PVC using a table saw (I did), then I can’t stress enough the importance of observing every safety precaution you ever heard of, up to, and including, wearing a lacrosse helmet over a hockey mask. See exhibit A below, which illustrates the effects of “kick-back”, and very nearly compromised the bilateral symmetry of my face.

Cutting PVC pipe with a table saw is like fishing with dynamite. In fact, I take it all back; don’t do this. It’s dangerous, it will prematurely wear down your saw blade, eat puppies, and make you sterile. But … if you’re willing to take a chance with your life, then build a wooden jig to firmly hold the pipe in place, use a fine-toothed blade, cut in warm weather to reduce the chance of splintering, and wear gloves and face protection. Or maybe try a chop saw. Hmm. Why didn’t I just use the chop saw?

A bit of 1/2″ foam board makes a decent substrate to keep the LEDs from rattling around. Cut a disk to the same inner diameter as the can (two inches, in our case). You want a snug fit, but if it’s too tight, then sand lightly around the outside of the disk.

A bit of 1/2″ foam board makes a decent substrate to keep the LEDs from rattling around. Cut a disk to the same inner diameter as the can (two inches, in our case). You want a snug fit, but if it’s too tight, then sand lightly around the outside of the disk.

Your disk need not be an exact circle, but it’s generally preferable that the substrate conform to the shape of the container in some fashion (cough).

To insert an LED, first poke a hole through the disk with a nail, then open the hole with a small circular file. A cordless drill would probably speed things up (he said, wondering about his fixation with small circular files). Make the hole a bit smaller than the LED case so it fits snugly, and insert each LED so the positive leads are facing the same direction.

If you sorted your LEDs by color, then you probably have five separate piles of red, green, blue, amber, and yellow. These can be combined to produce new colors. Trying out different combinations is a fun way to waste a lot of time.

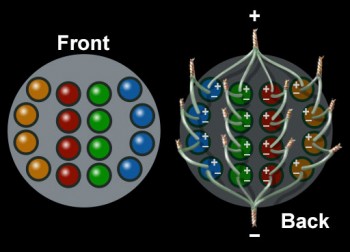

This drawing of a spiky Christmas ornament is, in fact, the wiring diagram for a 16-LED lamp.

This drawing of a spiky Christmas ornament is, in fact, the wiring diagram for a 16-LED lamp.

It consists of four columns of four LEDs, each wired in series. At the end of each series circuit is a positive and a negative lead. These are connected to form a parallel circuit. See our previous article in this series for a more in-depth discussion of this horoscopy.

Note, in this first photo, how difficult it becomes to determine the polarity of the LEDs when one has not properly marked the leads. Additionally, planning your wiring routes ahead of time, and inserting your LEDs all in the proper direction, will avoid the need for any “bridge” wires (cough hack).

Attach a long wire (from your bucket-o-wire) to the positive and negative leads of the assembled lamp, marking one of the leads outside the can (my positives are marked with red electrical tape), then connect to 12V to make sure everything works. After soldering all connections, it’s not a bad idea to wrap them in electrical tape to prevent any shorts. This would probably not be necessary if you cut your leads shorter. Apply some carpenter’s glue around the edge of the disk and slide the assembly into the can far enough that everything except the two long lead wires are fully inside the can.

Attach a long wire (from your bucket-o-wire) to the positive and negative leads of the assembled lamp, marking one of the leads outside the can (my positives are marked with red electrical tape), then connect to 12V to make sure everything works. After soldering all connections, it’s not a bad idea to wrap them in electrical tape to prevent any shorts. This would probably not be necessary if you cut your leads shorter. Apply some carpenter’s glue around the edge of the disk and slide the assembly into the can far enough that everything except the two long lead wires are fully inside the can.

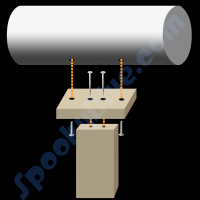

A two inch vertical beam (1x2x2) is attached to a four inch length of 1×2 lumber with two 1″ wood screws, forming a “T”. This is mounted to the can with two 1.25″ hex bolts. Drill holes for the mounting bolts through the wall of the can on either side of the lamp assembly.

Drill a hole through the base of the “T” large enough to accept a 1/4×1″ bolt (overkill, but I had a box of 1/4″ wing nuts). A washer and wing nut hold everything in place. Simply loosen the wing nut to adjust the angle of the lamp.

PVC end caps come in several varieties, from a $0.40 plastic insert, to a $3.00 end cover. However, for one whose list of quirks includes saving bits of plastic and other refuse in bins in one’s garage because “this might come in handy”, there are other options, especially if one is fond of a particular brand of grape jelly.

Drill a hole through the center of the cap and feed the wires through. If you use metal as a cover, insert a strain relief bushing, or rubber grommet, to protect the insulation from sharp metal edges. Apply a bead of caulk, or silicone sealant, around the inside of the cap and press firmly.

Our lens, a 2″ diameter disk cut from plastic sheeting (typically used in vacuum forming), is held in place with a 2″ PVC coupler and a bead of caulk. Any clear plastic would work just as well.

Our lens, a 2″ diameter disk cut from plastic sheeting (typically used in vacuum forming), is held in place with a 2″ PVC coupler and a bead of caulk. Any clear plastic would work just as well.

Why not just glue the end and lens cap using PVC cement? Because history teaches there’s a better than average chance we’ll need to get back inside this thing at some point in the future.

Place your 12V transformer in a (protected, waterproof) central location and run your cabling. Two-conductor cable is ridged on one side. Attach the ridged side to the positive lead of the transformer.

Place your 12V transformer in a (protected, waterproof) central location and run your cabling. Two-conductor cable is ridged on one side. Attach the ridged side to the positive lead of the transformer.

Attach a low voltage wire connector to the leads on the back of your lamp, taking care to note which side of the connector is positive. Place the positive side of the connector over the ridged side of the cable and firmly press the ends together. Metal prongs inside the connector pierce the cable jacket to make the electrical connection.

Part of the fun of any new project is answering the question, “I wonder if this will work.” Okay, that’s not a question, but the answer is yes, if your expectations are low enough.

Part of the fun of any new project is answering the question, “I wonder if this will work.” Okay, that’s not a question, but the answer is yes, if your expectations are low enough.

Okay, that’s not an answer. Let me put it another way. My expectations weren’t altogether realistic at the start of this project. Shadow Wood is located in a very dark hollow where ambient light is practically nil, and I prefer more illumination than these little guys alone can provide.

As accent lighting, however, the lamps work very well. We placed 12 throughout Shadow Wood, and once I got it into my head that their job was to provide little pools of color, I was happier with the outcome. Change your attitude, change your life. (gah…yes, yes, I know. Hypocrite, hypocrite, hypocrite)

The takeaway here is that 12 little LED Christmas light lamps won’t illuminate your cemetery like a honking 110V halogen flood. But they nicely fill a niche and only tap a small percentage of what the transformer can provide. Namely, nice steady current, which is exactly what high power (1W, 3W) LEDs enjoy most. Aha!

The takeaway here is that 12 little LED Christmas light lamps won’t illuminate your cemetery like a honking 110V halogen flood. But they nicely fill a niche and only tap a small percentage of what the transformer can provide. Namely, nice steady current, which is exactly what high power (1W, 3W) LEDs enjoy most. Aha!

Which brings us to why this project is probably a bad idea. Now, I suppose you can make the case that you could burn down your garage with a soldering iron, a definite consideration. And, of course, there’s the possibility that a flying bit of PVC shrapnel could make your sunglasses sit crooked for the rest of your life. But these are just hazards we face every day. The real problem here is weeds.

Which brings us to why this project is probably a bad idea. Now, I suppose you can make the case that you could burn down your garage with a soldering iron, a definite consideration. And, of course, there’s the possibility that a flying bit of PVC shrapnel could make your sunglasses sit crooked for the rest of your life. But these are just hazards we face every day. The real problem here is weeds.

Specifically, it’s the heading-off-into part that’s the trouble. There’s untapped potential in this project, both literally and figuratively. For instance, what will it take to make honest to gawd floods out of 3W LEDs? (Off into the weeds) With easy access to 12V DC, what other work can I make it do for me? (More weeds. Always more weeds)